For as long as I can remember, romance has comprised some part of every contiguous entertainment experience that has spoken to me. While certainly the values and nature of attraction and fulfillment changed as I grew older – as did my expectations in the nuances of my entertainment selections – romantic idealism has been with me from my earliest television and movie experiences. From amorous cartoon characters floating off the ground with a single kiss to reticent movie couples surrendering to mutual attraction that’s been beating them around the head and shoulders for an hour of on-screen hijinks, love has been a theme of so much quality family entertainment throughout my life – and for a generation or two prior!

And I grew up in the 80s. We were a cable family, and my parents really didn’t censor what my brother and I consumed (until they thought it would be too scary, but that’s another blog), so it wasn’t just classic musicals and Saturday morning cartoons that taught us the intricacies of romance. I followed Steve Guttenberg through his Police Academy misadventures (complete with boobies!!), Tom Hanks mackin’ on a mermaid, and Molly Ringwald waltzing her way through one John Hughes flick after another. I fell in love with Princess Buttercup and watched nobody put Baby in a corner. And I subconsciously took notes from Sam and Diane’s toxic 80s relationship.

But while I figured out pretty early on that I longed for a romantic experience in my life – that perfect poetry of true love and whatever came with it – so many of the variables were beyond my reach. Let’s take Ghostbusters, for example.

1984 was a big year in entertainment, and particularly for me. I was 8 or 9 years old. It was the year of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (damsel in distress, anyone?), The Last Starfighter (save the galaxy, get the girl!), Revenge of the Nerds (talk about cringe!), Purple Rain (um… wow), Dreamscape (man, did I want to have sex on a train – whatever that was!), and The Terminator (no way I could get the whole we’re-all-gonna-die-so-please-do-me-now vibe, but it was something). It was also the year that Peter Venkman, Ray Stantz, Egon Spengler, and Winston Zeddmore saved New York, and – you guessed it – Venkman got the girl.

nonconsensual lip-lockage in Dreamscape (1984).

Now it’s important to note that these were not movies about romance… it was just part of the package. Like it’s part of life. By this point in my youth, I had received the message loud and clear. But you also have to understand how we associate information with strong emotional experiences – and a movie like Ghostbusters had grabbed my imagination and refused to give ground. I was enthralled. And again… saved the day, got the girl. That’s the perfect ending, right!?

But as a boy there was one really harsh lesson life couldn’t communicate with any clarity. And that was the lesson of Ghostbusters II.

No… not that lesson.

A few years later, the anticipated sequel rolls around, and one glaring issue leapt from the screen with malice aforethought. After all that amazingness that culminated in the joyous finale of the first movie, Peter Venkman and Dana Barrett were no longer together.

While intellectually I knew that this was a thing – my own parents had even undergone a brief separation in the intervening years – it still felt like a betrayal. I couldn’t wrap my head around the central question of why. What had Venkman done to lose the girl?

You get that?! What had Venkman done? In the context of the story laid out in the film – and likely corrupted by my parents’ experience – I got that he’d been responsible. That his romance hadn’t been eternal, and that it was somehow his fault. And realistically, this was a theme that played out in a lot of similar tales in the entertainment world (particularly with any degree of confirmation bias); relationships were typically shattered by the irresponsible or outright treasonous behavior of the male counterpart. Like… if she was the prize for saving the day, then you had to deserve her to keep her.

Note that there’s a lot of uncomfortable constructs in that paragraph, much of it seeded by the hypermasculine bullshittery of the era: treating a partner like a trophy, absolving one person of responsibility in a failing relationship, and doubling down on archaic gender norms that sorely needed more disruption in the entertainment world at the time. But again, the lessons for a young man were driven home with abandon.

It was disenchanting, to say the least. It set a lot of expectations. Not just for young boys, but girls as well. Was the first 50 years of TV and its attendant cinematic offerings determined to reinforce gender stereotypes? Well… yes. In a way. Producers and filmmakers made stories based on what they knew. Even Star Wars with its one tough female protagonist started as a damsel-in-distress situation; George had started his personal journey with Flash Gordon and similar offerings, where the scantily-clad girl was always a pawn in the hero’s story. The viewing public wanted men to be men, women to be beautiful and demure, and they wanted their children to enjoy the same.

But my principal question is this: does youth-centered and family-friendly programming still carry the same messaging? Do our kids and grandkids fall in love as the characters do in their favorite shows? I know that we’ve come a long way toward dispelling the gender norms of yesteryear, but are our kids learning the right lessons? Do they even have so much romance in their stories? I genuinely don’t know.

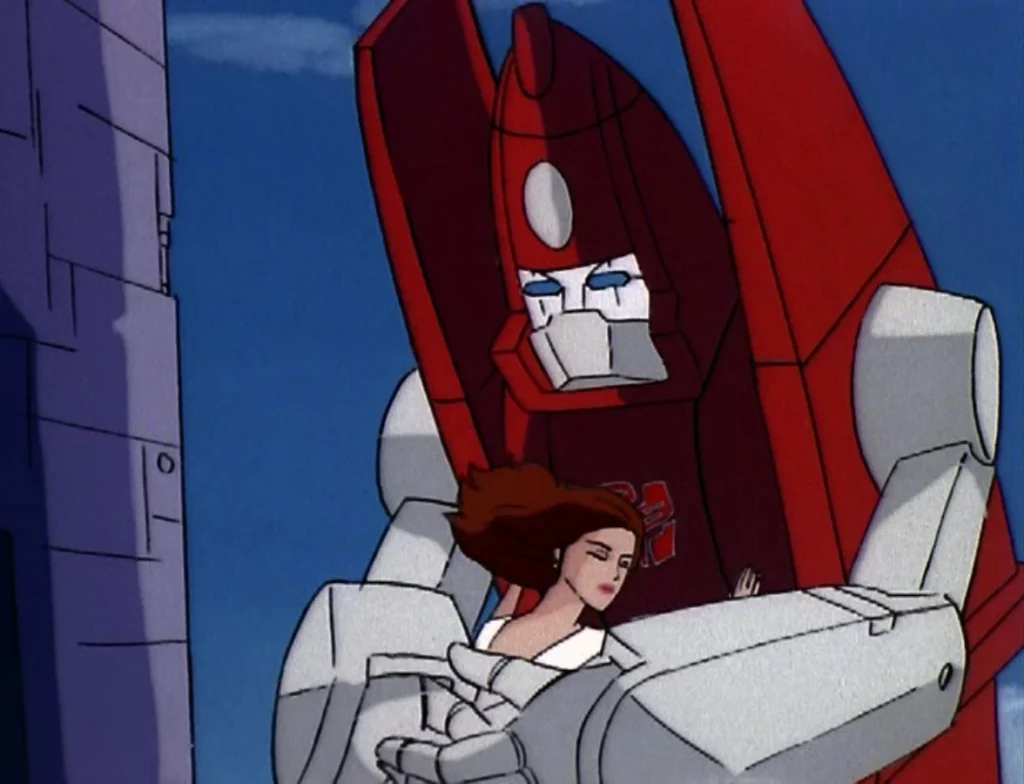

And yes, I know a lot of the shows I mentioned above weren’t meant for kids, but I don’t think that invalidates the experience of those that were. Even the second season of the Transformers cartoon had an episode with a girl falling in love with the Autobot that saved her life. And of course, I’m not referring to programming aimed at very young children; I don’t expect romantic messaging from Dora the Explorer or Dinosaur Train any more than we had in Sesame Street or The Electic Company.

My kids are largely past this age, and like my parents we don’t censor (but we’ve always tried to keep open communication going), so it’s something of an academic question to me, but I’m genuinely curious whether the urge for romance still thrives in the hearts of today’s youth.