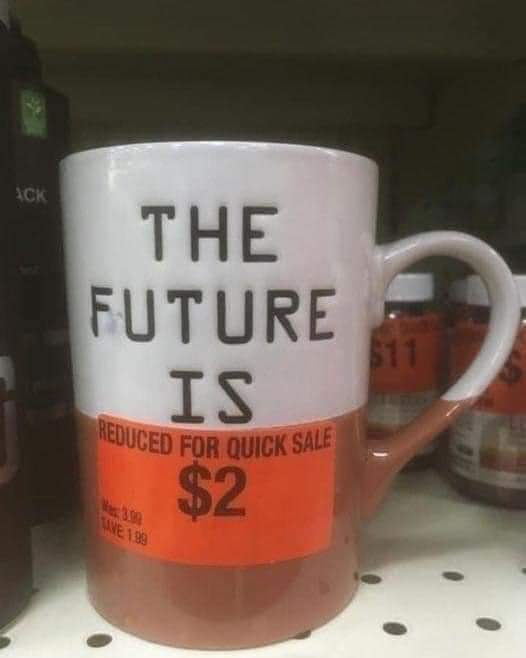

My friend Vanessa just shared this with our friend group, with the caption “I feel like this is the dystopia genre as a whole.” I laughed. It’s kinda true.

Then I realized something that tasted weird about that statement: the idea of “dystopia” as a genre.

Dystopian fiction has its roots in the very underpinnings of utopian science fiction. In the early era of sci-fi literature, authors imagined the future as an idealized state managed by political and social structures that reflected the author’s ethos. Dystopian evocations naturally portrayed the opposite, often with very cynical or subversive undertones. While utopian concepts celebrated mankind’s ability to transcend petty differences and transform their world into a realm of enlightenment, dystopian tales revealed the soft white underbelly of utopias built on corrupt and dangerous supports.

Needless to say, the latter evaluation is an outgrowth of the former and has become far more commonplace today. Which takes me back to the very foundation of the concept. Expressions of dystopia – corrupt power centers, inherent moral decay, the illusion of equality, and warnings about the trajectory of our social order – now pervade so many levels of modern entertainment. While initially developed as a means to provoke deep thought regarding the potential future of mankind, dystopias have now become an acceptable standard by which we measure the present. Even those of us who expound on a frightening look at the future we may very well be hurtling toward at terrifying speeds generally accept that our priority is to adapt and survive, that systemic change is a complete fantasy.

If you think about it, that is the polar opposite of the point of dystopian fiction.

I would propose that relegating dystopian fiction to “genre” status – which it certainly is! – marginalizes the art form. When it becomes passe and overwrought, we don’t actually see ourselves in the narrative. Sure, we see the extension of our society by proxy, but less as a thought experiment and more as a pickling kettle. We soak up science fiction and judge the story more than the premise. After all, we’ve seen nearly every plot structure and character evolution mulched over and again; the premise is either too far removed from the currency of everyday life or a foregone conclusion.

I grew up loving Star Trek. Roddenberry’s vision of the future of humanity was purely utopian. We lived in a world of peace and plenty. We had fought our wars and come out the other side stronger and ready to expand our personal horizons. We made giant space vessels for purposes of science and exploration. When we fought it was with violent cultures that had yet to achieve a similar state of enlightenment. As the franchise advanced the clock further, however, into the era of grunge music and the Gulf War, we saw increasing stories of subversion and human failing. The levers of power would fall into the wrong hands, and well-written episodes would often raise ethical questions with no clean answer.

From Deep Space Nine ssn4 episode “Paradise Lost”.

While Star Trek routinely held us to a higher standard from the very start – a position that has admittedly wobbled quite a bit from one entrant to the next – the lessons are now less visible to younger fans who no longer see the franchise’s alien warmongers, social stressors, profiteering, terrorism and intrigue reflected in today’s society. At best it starts to feel like an informed plot point we’ve seen a million times before, at worst it’s virtually satire.

And to my previous point… we are so inundated with dystopian story beats today that we no longer find as much value in entertainments that don’t have them. Corruption, manipulation, and inequality are part of our world, and stories that don’t reflect that are just unrealistic. I host a podcast where we talk about our favorite movies, and while sometimes we range into discussion about the implications of a filmmaker’s vision, our conversation typically rounds the maypole on performance, visual effects, and story choices that are made to move it along. I mean… why focus on the dystopia. That’s just normative.

We understand the inherent risk of the surveillance state recommended by George Orwell’s writings and the elements of social control we’re rebelling against in A Clockwork Orange and Hunger Games. We get the threat of totalitarian governments a la Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale or even Lois Lowry’s The Giver. We get it. And we rate it for it’s entertainment value.

Because crying ourselves to sleep at night f’ing sucks.

So, yeah. Dystopia is a genre.